Paolo Boni’s tools in his workshop, 7 Impasse du Rouet Paris 14th © Marie-Laure Picard

My engraving work, by Paolo Boni

Paolo Boni’s graphisculpture, an original process, by Carla Boni

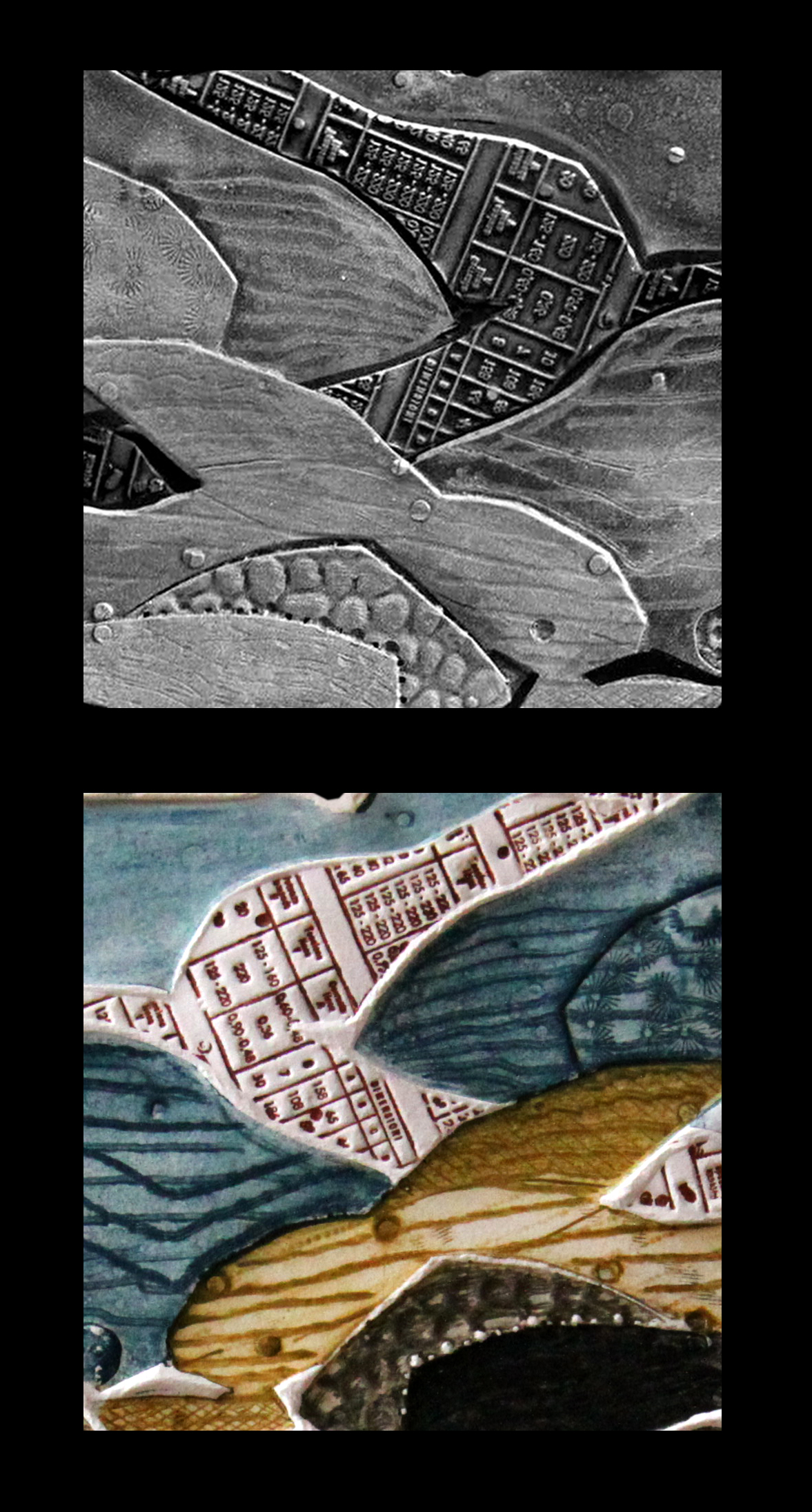

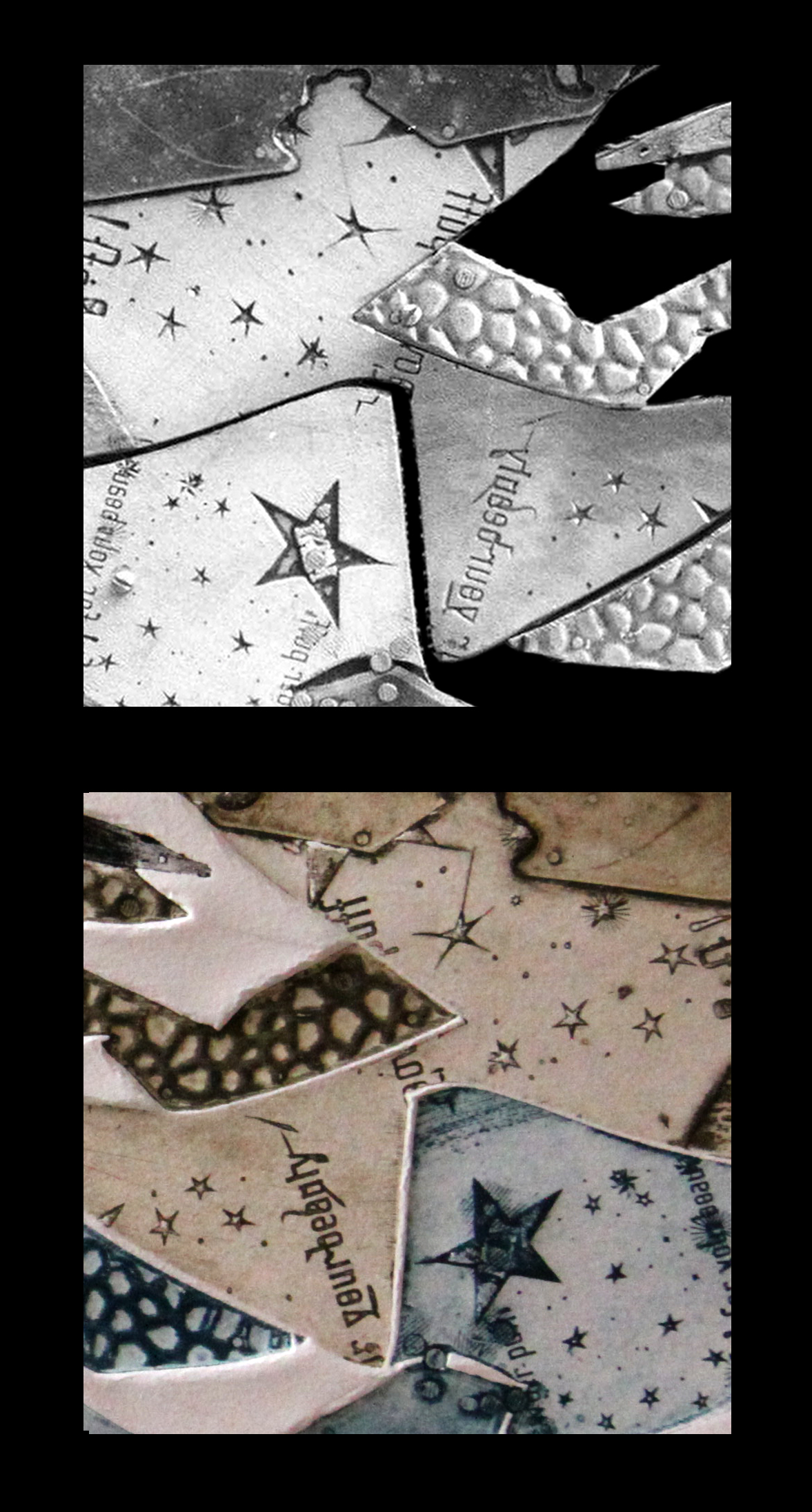

Print of the Zodiaque graphisculpture, 1969

Matrix of the Zodiaque graphisculpture, 1969

My engraving work, by Paolo Boni

“I built myself a novel set of tools that answered the need of a direct hold on metal, as whole and wide as possible: files, of which the head was thinned in the shape of a rectangular tongue sharpened at its end, bit flatly on the whole surface or side, deepening the cuts. Cutters mounted on drills, to obtain modulation: embossing, sockets, imprints, that I also get from the use of pre-made metals.

I didn’t want to neglect the new possibilities that cutting or hollowing out the metal sheet offered: by cutting it on the outside shape of the sketch, the geometric rigidity of the frame is broken, the margins start communicating with the inside, the texture of the paper is integrated during the printing process, the composition stops being limited by the format of the engraved surface exclusively.

From the combination of the two, three, four cut-out metal sheets in different riveted metals – zinc, brass, copper, aluminium, iron – resulted in not just the relief itself, but also nuances in variations due to the different pressions and to the specific colour reactions depending on the type of metal used. In the case of the polychromatic prints, my metal sheets are constituted, like jigsaws, of dissociable elements anchored separately and then re-assembled: the print can be made in one go, without the risk that the inks might mix.

In engraving I found what is probably to me the condition of plastic imagination: the possibilities of reassessment, at the most basic level of the treatment and the choice of textures – but perhaps as well, without the enchanting colour of playful shapes, an answer to the need to break, with violence, metal’s glacial silence. Satisfying the rites of an elementary aggressiveness, my fellow countrymen of the past, the Tuscan master workers, forged, chiselled, assembled, piece by piece and with an infinite concern the terrible and wonderful armours in exile at the Metropolitan Museum.”

Paolo Boni

Superposition, graphisculpture sheet, 1967

Paolo Boni’s graphisculpture, an original process, by Carla Boni

Paolo Boni’s engravings, called ‘graphisculptures’, are his own original adaptation of the traditional idea of what we call engravings or prints. It was in 1970 that Alfonso Ciranna, a gallerist and art critic from Milan, first put the name ‘graphisculpture’ onto Boni’s work, a term he had come up with after being inspired by the expressive quality of Boni’s engravings.

Paolo Boni’s first engravings date back from 1957. He continued working on engraved works throughout his life, up until the 2000s. He learned engraving in Stanley William Hayter’s Paris workshop, but Boni left him quite early on after having broken one of the main rules the artist had taught him: he had pierced the sheet of metal. From the beginning, Boni was captivated by revealing the white of the paper through the engravings by poking holes in the metal sheets, and it rapidly became an essential aspect of his artistic process and his distinctive trademark.

Boni’s fixation with relief continued steadily through all his work and in all mediums, from the graphisculptures to the wood pieces he shaped and painted towards the end of his life.

As early as 1960, he cut metallic plates and re-assembled them using home-made rivets. What was at the start a simple metallic sheet evolved, and in just a few years became jigsaws composed of various metals, shapes cut and then positioned one on top of the other. These shapes still remained separate so that they could be anchored independently, deconstructed and then reassembled.

The rivets were minutely created using nails: the metal plate was pierced using a drill, the nail put in, then the plate was flipped and the nails’ heads cut and hammered. Boni also used printing plates which had become obsolete once they had fulfilled their purpose of printing newspapers, ads or magazines, before the invention of phototypesetting and eventually of the computer. Additionally, he incorporated all sorts of tools in order to mark and imprint the metal: shears, files, engraving tips, awls, drypoint needles, punches, grinders, milling machine parts…

The metal sheet wasn’t the sole purveyor of artistic expression in the way a classical print is; there was also a diverse combination of metals and of everyday objects in Boni’s work. He conjured up a whole world of signs and symbols of his time, reinterpreted to give a new soul to his graphisculptures. Boni added all sorts of metallic objects he found on the street as he saw fit: sieves, belt buckles, coins, shoe heels, can lids, radiator grills, barbed wire, furniture locks, numbers and letters, etc. Some of these incorporated objects bring a humorous element to the artworks once they are identified by the viewers and they keep with the playful and mischievous personality of the artist. These everyday objects lose their original purpose, realistic or industrious, and become a part of the artwork. They are poetic nods that punctuate the mechanical assembly of the piece.

The plate’s entire relief was transposed on the paper. The impression was not shallow, it truly reflected the palpable, 3D quality of the metallic artwork. If we were to show the wrong side of the print to a grazing light, we would be able to witness all of the work’s depth. Boni became a master at juxtaposing metal sheets and gauging the right thickness so they wouldn’t be pierced through and yet still achieved the maximum depth possible, by using specific types of resistant papers such as Velin d’Arche or Rive paper, both made using traditional methods.

In 1964, Boni went from monochrome engravings to integrating several colours during the printing process. Thanks to previous experimentation, he had discovered the ways in which the use of some metals altered the colours through different chemical reactions. He used zinc, copper, brass, aluminium, and steel. Unlike steel, an inert metal, brass, zinc, and copper could dramatically transform in colour and intensity. With knowledge of metal oxydations, Paolo Boni could choose shapes and areas on which to apply specific nuances.

Artists would frequently go through intaglio printing artisans to print their works. Boni often worked with his nephew Mario who was a printer who used the intaglio technique, so he could test out different printing settings and methods for his graphisculptures, until he reached the final proof. This allowed him to modify the plate before the final printing if the result of the tests were not quite satisfactory. Once the final proof was approved, the intaglio printer could then print as many identical works as desired. That number could go from just a dozen to fifty depending on whether it was an order from a gallery or from the artist.

Boni’s printing method allowed him great freedom. As the graphisculpture plate was itself made up of different plates arranged like a jigsaw, it let Boni apply the ink to each piece independently with a different colour or shade. The plates were afterwards reassembled in order to create a wide diversity of colours in one go. For the inking, the intaglio printer used a range of gelatinous rollers of varying hardness depending on the desired result, as well as brushes for smaller areas.

Intaglio printing required specific inks. Linseed oil could be added to accentuate the transparency effect, or turpentine to play with oxydation. During the inking process, different ‘settings’ could be manipulated and tinkered with; the amount of ink applied, the tautness of the tarlatan canvas, or the use of paper in its place. These could create dozens of shades and a wide range of halftones that produced unexpected transparencies. Once the jigsaw was reassembled on the printing press, the paper was delicately lain on top of it after being minimally dampened, so it could absorb as much colour and texture as possible without cracking. The print thus obtained was both multicoloured and had significant reliefs in only one pass, which earned it its name of graphisculpture.

Carla Boni, October 2025

Details of the Zodiaque graphisculpture’s engraved sheet and its print